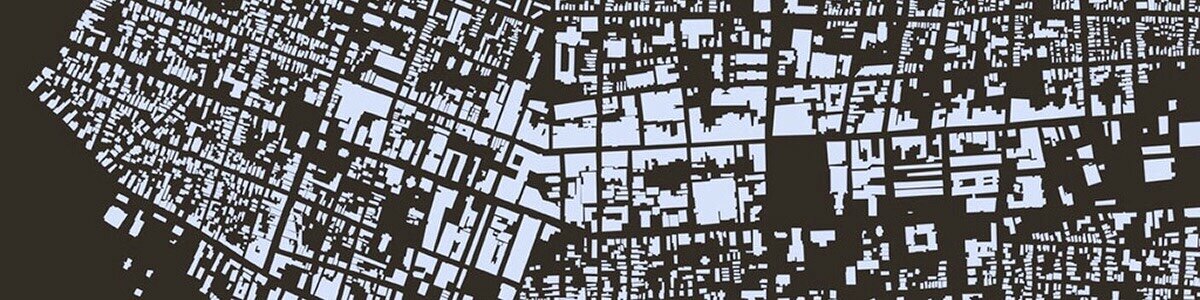

Nolli Diagram (Charleston, SC)

Albert Einstein once said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” In order to solve our present challenges with growth, transportation, sustainability, consumer market demands, demographic changes, and how these items affect the design and development of our built environment we have to think and work differently. If we want to solve the problems that we currently face we can’t expect to do so by using the tools that led us to where we are today.

We must recognize that development in this country is shaped by particular land use policies that govern it. Land use policy has a direct impact on such areas as physical appearance, human behavior, economic development, and environmental sustainability. All of these carry over to the everyday experience in our communities. Our system of land use policy is made up of regulatory, economic, and design related forces which manage the arrangement that our built environment takes. No matter how badly we may want or need to see change, if we continue to use the same thinking, system, and tools, our built environment will NEVER reflect anything different than what we already have.

Euclidean Zoning is the standard for land use policy in the United States, and has been since the 1920’s. It is the primary tool used by local governments to establish how our built environment takes shape. Euclidean Zoning’s primary focus is on regulating USE and DENSITY.

Source: Peter Katz – Form-Based Code Institute

If you simply regulate to prevent the BAD you are not allowing for the encouragement of the GOOD. Such regulation leaves little room for communities to define what they want to be, and merely defines what they cannot be. This creates a tendency toward nameless, placeless, unsustainable environments. One consequence of policy that neither specifies what communities want nor acknowledges what makes development profitable are projects of poor quality that satisfy neither community desires nor the maximum potential of development. It is curious that policy with the intent of preventing bad development fails to produce good development, but what we’re seeing on the ground confirms that in congruence between intent and result the primary tool used by local governments is to establish how our built environment takes shape.

Euclidean Zoning’s primary focus is on regulating USE and DENSITY. While it touches on FORM, it does so at a subordinate level, often only as an afterthought in the overall process. This forces development decisions to be addressed in a subjective and reactionary manner. Because Euclidean Zoning is proscriptive by nature, it tells the development community what NOT to do, rather than offering a prescriptive vision that invites what can be done. The result is the community is left with uncertainty as to what the end product will be because FORM is not adequately considered. Such uncertainty leaves Planning Commissions and City Councils focusing on “what the project is going to look like” and “how will it fit into the community”. The irony in this is that these are FORM related questions because the current system doesn’t adequately address those issues.

Form-based codes offer an alternative to zoning for governing land use. It is a regulatory system which places a more direct focus on the urban form that is created through development practices, while emphasizing the physical character of development and de-emphasizing the specific regulation of land uses in general. Form-based codes don’t ignore USE and DENSITY, but rather place them in a supporting role to FORM. USE and DENSITY become subject to the FORM which is determined by a community’s vision of what the desired outcome should be. The end result with form-based codes is a greater degree of predictability for the municipality, the developer, and the community at large.

Source: Peter Katz – Form-Based Code Institute

Form-based codes have shown tremendous promise in promoting placemaking, encouraging infill, and integrating land use and transportation. Form-based codes have also proven effective in shortening plan review times due to their clear and prescriptive nature.

If we want different results than the ones we are presently getting, we need to change the way we operate. It doesn’t require the abandonment of Euclidean Zoning in lieu of form-based code. Our land use policy system simply needs to be augmented in order to better include the aspects of FORM. Form-based codes offer just that kind of opportunity!